A rock opera on Imelda Marcos

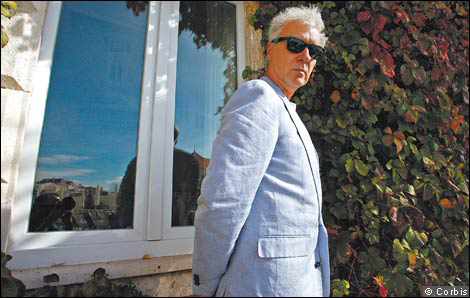

David Byrne is no stranger to eccentric projects. The former Talking Heads frontman has turned an abandoned Manhattan ferry terminal into a vast musical instrument, written a book about his travels around the world with his fold-up bicycle and mounted an art exhibition devoted to his obsession with chairs. His new album is possibly his oddest undertaking yet: a double CD rock opera about the rise and fall of Imelda Marcos. Over 22 songs, Here Lies Love describes Imelda’s journey from humble provincial girl to larger-than-life consort of Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos before their flight into exile in 1986. It comes with a 114-page book containing photos, lyrics and Byrne’s explanatory text, takes 90 minutes to listen to and knocks spots off Evita. The inspiration came to Byrne about five years ago. “I read somewhere that Imelda loved going to clubs like Studio 54 and had a floor of her New York townhouse converted into a disco,” he says. An idea struck him: might dance music’s escapism provide a key to understanding the mentality of a kleptocrat who embezzled billions of dollars from her nation, yet still asserts she did nothing wrong? “I thought, ‘Wow, here is somebody who was in a position of power and created their own little bubble world.’ I wanted to delve into what makes this public person tick, what drives them, how they can be in such deep denial about some of the things they’ve done,” says Byrne, 57, sitting in a London hotel room sipping a cup of tea. The New Yorker is a study in monochrome symmetry: a vertical quiff of white hair, black shirt and trousers, spotless white trainers. Back in the late 1970s, when Imelda Marcos was boogying at Studio 54 during lavish shopping trips to New York, Byrne was making waves in the city’s punk scene with Talking Heads. The cerebral, slyly catchy art-rockers formed in 1975 after Byrne dropped out of art school in Rhode Island. The band split in 1991 but Byrne’s reputation for high-concept pop has continued in his solo career. An avid collaborator, he has worked in the past with Robert Wilson, Brian Eno and Twyla Tharp. Here Lies Love matches him with a rather less highbrow figure – Fatboy Slim, aka British DJ Norman Cook. The results, as with the best of Byrne’s work, are both intelligent and highly entertaining. With beats largely supplied by Cook, the music skips through disco, funk, Broadway and kitsch exotica. The style is deliberately western. Although Byrne is an influential promoter of world music, setting up a record label devoted to it in 1988, he makes no pretence at incorporating authentically Filipino musical themes. “Sadly to a large extent a lot of Philippine culture was wiped out,” he says. Colonised by the Spanish and then by the US, it remains a vital US military staging post in the Pacific. “The force of American consumer pop culture basically wiped out everything there, at least on the surface.” Byrne’s ambivalence about US pop culture surfaces on Here Lies Love’s “American Troglodyte”, on which he imagines a Filipino gazing at US soldiers “wearin’ those sexy jeans” and “listenin’ to 50 Cent”. The mingled fascination and contempt is a theme dating back to Talking Heads’ Middle America-bashing “Big Country”. “It’s very confusing. There are aspects I love and aspects that I completely hate and sometimes they’re embodied in the same thing,” says Byrne, who was born in Scotland, emigrating with his family when he was two. He went to the Philippines to research the album and discovered an “amazing” Filipino ability to mimic western pop music. “You pass bands on the beach and think, that’s Neil Young.” Here Lies Love cleverly evokes a country so saturated with western pop culture that two rival guerrilla groups currently operating in the islands call themselves the Monkees and the Beatles. “They’ve absorbed all this global pop music and made it their own.” The album’s plot centres on Marcos and her childhood servant-cum-surrogate mother Estrella, whom Imelda ruthlessly discards on her way to the top. Instead of the same two singers singing their roles throughout, the 22 songs feature a large cast of female vocalists, including Florence Welch, Martha Wainwright, Cyndi Lauper and Tori Amos. Byrne’s vocals crop up only twice: on one song he sings the role of the assassinated opposition leader Benigno Aquino, who dated Imelda in their youth but made the fatal error of jilting her. Many of the lyrics are based on real-life quotes from Imelda. Kitsch sayings about love and beauty predominate: Here Lies Love is the inscription she once said she wanted on her tombstone. Her notorious collection of more than 3,000 pairs of shoes, discovered after the Marcoses were overthrown, is deliberately not mentioned. “For me the story’s over when they flee,” Byrne says. The widowed Marcos returned to the Philippines in 1991, but Byrne did not meet her during his research visit. “She had the flu, so she couldn’t meet. But I was wary of meeting her. I though it would be exciting but I wouldn’t learn anything, I’d just be an audience.” In the west Imelda Marcos is often treated as a camp, comic character. Yet there was nothing camp or comic about the scale of the Marcoses’ corruption or the political violence they sponsored. When an early version of the song cycle was staged in Australia in 2006, Byrne was criticised for playing down Marcos’s crimes. “There might be some truth to it,” he concedes, “although my response is that if you want to understand someone you have to empathise with them up to a point. You don’t have to excuse what they did but you have to put yourself in their frame of mind.” The danger is that by focusing on Marcos’s personality – she was, Byrne writes in the book accompanying the album, “driven by psychological angels and demons” – Here Lies Love risks contributing to the cult of personality she and Ferdinand Marcos assiduously cultivated. The 80-year-old former first lady remains a political force in the Philippines: she is standing for parliament in elections this May. “If I ever get to do a theatrical version, I’m still not sure how to bring the embezzling and all the other things into it in a way that isn’t just boring expository stuff or a character accusing her, which again makes it a little too black and white,” he says. “I don’t really address it directly, I address it obliquely.” The subtle approach has advantages too. Here Lies Love’s beguiling music and vivid lyrics evoke Imelda Marcos’s corrupt, seductive glamour. Even today she is popular in the shanty towns of Manila. “You find yourself simultaneously disagreeing with what a person is doing but empathising with the feelings that they have,” Byrne says. “So you find yourself in conflict. But the song, because it’s pop music, you naturally kind of go with it, but then you find yourself going with something that is against your better judgment. And that,” he concludes with relish, “is when it gets interesting.” |